Who's *Really* A Christian?

It's not uncommon for someone to ask if a person is "saved" or "really a Christian" or "actually knows Jesus." You may hear claims that someone "can't be gay and a Christian" or that "there's no way Trump is actually saved."

What's slippery about this question is that it could refer to several distinct concepts that are all being collapsed into one deceptively simple question.

Here are at least six of those concepts:

- Identification: Does someone voluntarily identify as a Christian?

- Behavior: Is someone behaving in a way that resembles the way of Jesus or, at least, a way of life initiated by first-century Jews and Gentiles called Christianity?

- Belief: Does someone believe in a set of theological tenets that are recognizably Christian?

- Belonging: Does someone belong to a community that is called Christian?

- Born Again: Has someone been born again and is therefore conscious of and voluntarily participating in the Christian faith?

- Post-mortem State: Will someone be part of a paradise-like afterlife?

Let's get into specifics.

Identification

The most basic, barebones way to ask and answer the question about whether or not someone is a Christian is simply this: If asked, would the person say they are a Christian? If yes, then yes. If no, then no.

In other words, "Christian" can be as simple as a demographic identification on a survey.

The issue, of course, is that the word Christian begins to lose meaning if it's no longer connected to a historic set of beliefs, practices, or communities. Someone could lie, cheat, steal, pilfer, pillage, incite an attack on the Capitol, etc., and—merely by checking "Yes" on a survey—still be considered a Christian. This is the problem that many Christians have with Donald Trump. There are very few examples one could point to in the former President's faith, life, or beliefs that seem at all similar to historical or modern expressions of Christianity. But the felonious fomenter of insurrection has said that he is a Christian. What does one do with that?

I could simply refuse to believe him. And, for a counter-example, that is what non-affirming Christians do with LGBTQ Christians. There are tens of thousands of gay Christians who actively participate in churches, serve their communities, and refuse to attack the Capitol. However, other Christians would refuse to accept LGBTQ people's self-identification as Christian because of their sexual orientation or gender.

This question runs alongside the "No True Scotsman" fallacy. Millions of Christians support abortion rights. Millions don't. Each could claim of the other, “No true Christian would support such-and-such a policy…” But which Christian gets to decide who is the true Christian? Perhaps they cancel each other out, and there are no true Christians.

If someone calls themselves a Christian, then I think, at least in terms of demographic identification, they are indeed a Christian. If you tell me you're a Christian, I will believe you.

Behavior

But perhaps what someone is asking is not merely about identification but about how someone lives their life. Their orthopraxy. Are they living their life in such a way that someone could compare it to how other Christians—perhaps the first Christians—have lived throughout the centuries and see some sort of match?

This is just as tough of a question because there have been a ton of different Christians who have lived a ton of different ways. We're not too far off from the" No True Christian" sort of fallacy.

But you could likely find a consensus on a few basic behaviors. For instance: prayer; some sort of engagement with a holy text; some kind of attendance of worship services; perhaps some form of generosity or service.

Then again, lots of folks pray, engage with a holy text, attend a worship service, and are generous...and are Jews, Muslims, or Hindu.

Perhaps the behavior needs to line up with the fruit of the Spirit of Galatians 5: love, joy, peace, kindness, etc. But there are plenty of loving and kind people who aren't Christian. And plenty of Christians who aren't particular kind.

So perhaps the behavior must be associated with—

Belief

Perhaps what we mean by "Are they Christian?" is "Do they believe in what Christians believe in?"

On the one hand, I do believe that there is a consensus of what Christians have typically, historically believed in.[1] But for just about every tenet of belief you could list, you can probably find a community of self-identified Christians who didn't believe in some particular idea.

You could probably claim that Christians believe something about the importance of Christ. But that's about as far as you can go without running into someone who disagrees. There are Christians who think Jesus of Nazareth is divine, some who don't. Some who think he's alive today; some who don't. And so on.

The famous phrase trying to clear this up is, "In essentials, unity; in non-essentials, liberty; in all things, charity." [2] But who gets to determine what the essentials and non-essentials are? That question leads to:

Belonging

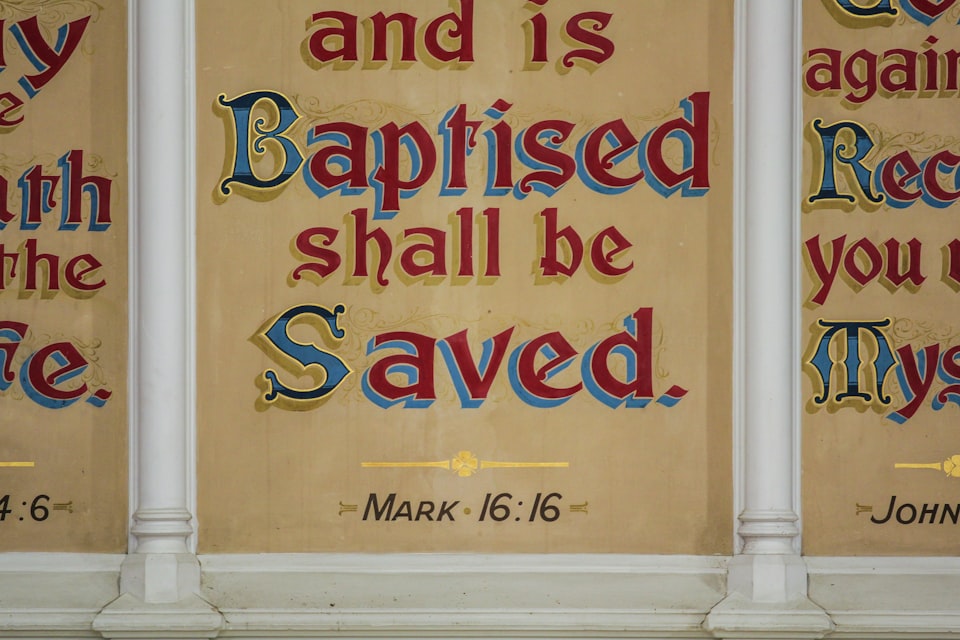

Perhaps the definition of Christian has more to do with a communal identity than anything else. In churches that practice infant baptism (Lutheran, Reformed, Methodist, Presbyterian, Roman Catholic, Orthodox), salvation is not something one chooses. It is an inheritance you are born into. Baptism is not about what a person decides; it is a recognition of what God has already done.

Here, we are venturing into biblical themes of covenant communities, and perhaps the closest to how I myself would define "salvation." An ancient Israelite was "saved" by virtue of having been exodus'd from Egypt—or being the offspring of someone who was. Salvation was not about belief, identification, or even (at first) behavior. It was a fact of history.

My 5-year-old son could be counted among "Christians," even though he has made no profession of faith and could not articulate theological beliefs much more intelligible than his belief that the gifts under the Christmas tree were delivered by Santa Claus. But, by his belonging to my particular family, a demographer would probably count him among Christians.

Children eventually grow old enough to choose if they will belong or not. But even then, a child may choose to disown their parents while the parents still call their child their child. A person may decide to no longer affiliate with a church, but the church could still count them as a member—either for poor record-keeping reasons or because the pastor believes that a person's belonging extends beyond one's volition.

The New Testament writers conceived God's people as a new ethnicity and family, more potent than even one's genealogy. "The blood of the covenant is thicker than the water of the womb."

Born Again

Perhaps there's a person who checks all of the above boxes. They identify as a Christian; behave and believe in a way that looks Christian; and belong to a community that identifies as Christian.

Wildly enough, however, another group of Christians may look at that person and still say they aren't truly a Christian because they haven't been "born again." Born again can mean lots of different things. I'm using "born again" as a signifier to identify who's part of the "in-group" or not. Examples include: ecstatic experiences (e.g. baptism by the Holy Spirit); ways of dress; specific spiritual gifts (such as tongues); particular Bible translations (e.g., KJV-only); or belonging to specific denominations (for instance, Twelve Tribes insists that you must denounce all your former religious experiences as false).

Born again can merely refer to "making a personal decision to follow Jesus." But often, the churches that use this language are very closely adjacent to—if not themselves—highly authoritative, fundamentalist expressions of faith.

Counter-intuitively, these signifiers have the effect of creating communities that move further and further away from recognizably Christian beliefs or behaviors. But they still count themselves as Christian due to the immense weight put on the born-again signifier. This effect, at least in some part, accounts for the incredible number of born-again Christians who 1) don't go to church; 2) don't pray or study the Bible; and 3) see Donald Trump as the infallible savior of the United States, if not the world.

Post-Mortem State

Finally, if someone asks if so-and-so is saved, they may merely mean, "Are they going to heaven when they die?" This, unfortunately, reduces Christianity down to a form of fire insurance, i.e., a way of protecting against an unpleasant afterlife.

However, this misses the point of Jesus' ministry and the overarching message of the Hebrew Bible and New Testament, which is about the redemption, renewal, and reconciliation of all of creation. The Bible seems fairly uninterested in answering "Who's going to heaven?" and far more interested in "How will this old world be repaired?" To ask, "Is so-and-so going to heaven?" affirms a theology foreign to the pages of Scripture.

Now, as a pastor, there are significant moments when a grieving person simply wants to know if their dead loved one is in a place of comfort or torture. The scope of this article limits what we can say here, but my answer is, for every person, "God's mercy endures forever. God is always in the work of healing and making someone whole, and that work does not cease upon death, regardless of their beliefs or what particular religious club they happened to belong to."

So...Who?

The fact is, I ultimately don't really care who fits under the label Christian or not. I think there are far more important and interesting questions:

- How do they treat people? Are they kind? Loving?

- How are they contributing to systems of harm?

- How are they helping dismantle them?

- Are they helping "mantle"[3] new systems of liberation?

- Do their beliefs have any sort of correspondence to reality?

- Does someone's beliefs lead them to cause harm to themselves or other?

- Have they committed themselves to a community?

- What are those communities values?

- Have they agreed to be held accountable to those values?

Don't get me wrong. I think questions of belief, belonging, and behavior are important. But the fruit is more important than the label.

Member discussion